General High-Impact Teaching Practices

These practices can be used in most settings and with most course subjects (with adjustments as needed).

As a rule, HITPs will be activities that are structured to help students:

- Work with the content they are learning

- Think more deeply about the content through application, analysis, creation, or evaluation (of the content)

- Develop their own understanding of the content

- Connect units of understanding (course content, personal experiences, content from other courses, etc.)

Individual Student HITPs

-

Retrieve Prior Information

A powerful way for new information to "stick" is to ask students to bring to mind other information they might know - or that is related to - the upcoming topic. This prior information might be:

- An experience they've had involving the topic. Example: For a unit on aging and memory: "Have you known someone with Alzheimer's or other cognitive decline? What symptoms do you know about, either from the media or with someone you know?"

- A parallel (and commonly known) topic that shares many similarities with the one you're about to teach - an analogy. Example: Ask questions about how balls bounce (or ask students to write down their observations) before teaching about how radars work.

- Past content from the class that leads up to the new information. Example: Ask students to complete refresher problems on chemical functions before introducing next steps that help them solve chemistry problems.

Why this works: This method of retrieving students' prior knowledge helps them connect the known to the unknown.

Methods:

- Ask students to complete a survey (before class, or embedded on a slide) with their responses

- Have students jot down thoughts related to prior knowledge and then share out or turn them in

- Create problem sets or quiz questions that require students to use prior knowledge that is important to upcoming new information

These methods can become more powerful in groups, as students can overcome uncertainty, learn different perspectives, and fill gaps in prior knowledge through small-group discussion. Consider allotting 5 minutes more for students to share with a neighbor or small group (see Think-Pair-Share, below).

-

Reflections

Following an information segment, unit, or module, ask student to reflect on one of the following:

- The value of what they learned (to career, life, self, understanding of the field, etc.)

- What they know now that they did not know at the start of the course

- How they prepared and performed on any assessments (and plans for next time)

- What challenged them most about the content

- What questions they have now about the field, given what they have learned

-

Perspective-Taking

Instead of asking students to simply draw their own conclusions from their personal standpoint, encourage the understanding that perspectives can create bias in thinking. Using a topic that lends itself to diverse points of view in its interpretation, create an assignment wherein students are provided two (or more) brief descriptions of roles (i.e., perspectives) they are to take as they answer questions you might pose.

Example:

Review and consider the campus “no-smoking” policy. Next, consider this policy as if you were the following people:

- Person “A”: A faculty member who is trying to quit smoking.

- Person “B”: A student who has smoked for 10 years and has classes on campus most of each day.

Taking each role in turn, discuss answers to the following questions:

- If I were Person A/B, what sorts of things would I think would be important to consider

about the no-smoking policy?

- If I were Person A/B, what would my judgment about the policy probably be?

- If I were Person A/B, what kinds of evidence would I likely be looking for in support of my arguments?

- If I were Person A/B, what kinds of evidence would I likely avoid or not want to know about?

- If I were Person A/B, what assumptions might I make?

- If I were Person A/B, what would be the implications or consequences of this policy for me?

-

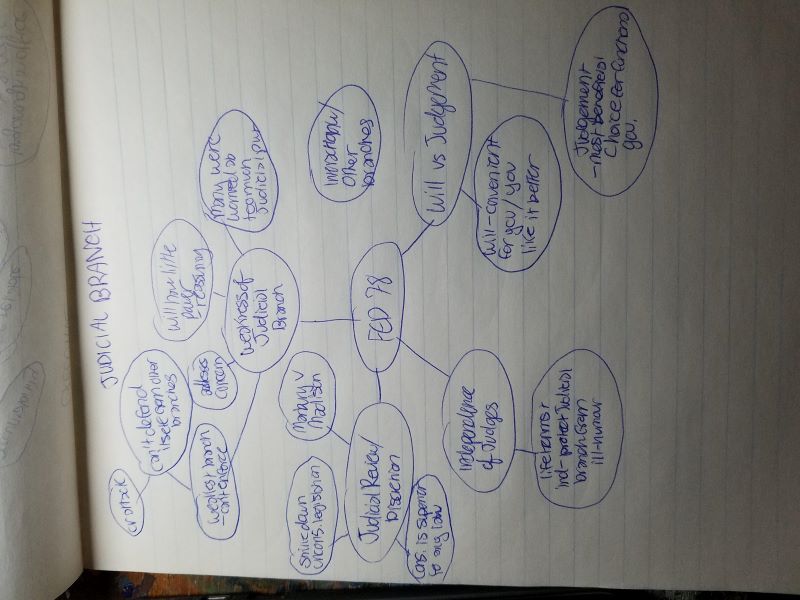

Concept Maps & Outlining

For a unit or module, have students create and then periodically revisit and add to a concept map.

Concept maps can be messy and informal; topics and details are added to show the interrelationships among concepts. They are connected with lines and arrows as relationships are identified.

Find examples of the many forms concept maps can take here.

Similarly, asking students to create an outline of course concepts, nesting related items together, encourages them to think about the organization and relationships among concepts.

Like concept mapping, outlining can be effective for helping students see how information nests together or interrelates.

It's important to allow students time to figure out this organization on their own, instead of telling them yourself. Perhaps they could take 5 minutes to generate an outline, then share and compare with a partner and refine their organization.

Outlining not only assists students with cognitive organization of your course material, but also requires them to more deeply consider the information, leading to better retention of what they are learning (and retrieval of that information later).

-

Visual Representations

In their notes, or perhaps after providing them a worksheet with specific topics, processes, or cycles noted, have students represent each of the concepts with visual symbols or digitally-located (pasted) images.

If drawn during class time, it is important to let students know that quality of the drawing is not important.

-

Visual Comparisons

Have students turn a blank sheet of paper 90 degrees and draw a line down the center. Give them a label for each half of the page: Two concepts they are learning that may share similarities or might be very different from one another.

Students draw visual representations of each concept to either distinguish them from one another (for similar concepts) or demonstrate their similarities (for different concepts).

Follow-up is important to explain their images. Choose an option:

- Share their results with the class (works best in small classes)

- Share with a partner or small group

- Create a short video explanation (max 3 minutes) to upload to you or post to the class in a dicussion on D2L

-

Thinking Routines

Harvard's Project Zero introduces a number of "thinking routines" you can incorporate in your class to make thinking more visible and impactful for students.

These routines are numerous and vary according to the goals you have for students as they approach their thinking about the material.

The routines can be as impactful in small groups or in online discussions as they can be as individual prompts or mini-assignments in class. They are great ways to follow-up some exposure to new material, permitting students to more actively process what they are learning.

Small Group HITPs

Small group - or whole-class - HITPs have an added benefit of social interaction.

Social interaction is considered important by some learning theorists, as it offers peer-level scaffolding, sharing different perspectives, a sense of community, and a low-threat way to test out ideas or thoughts.

-

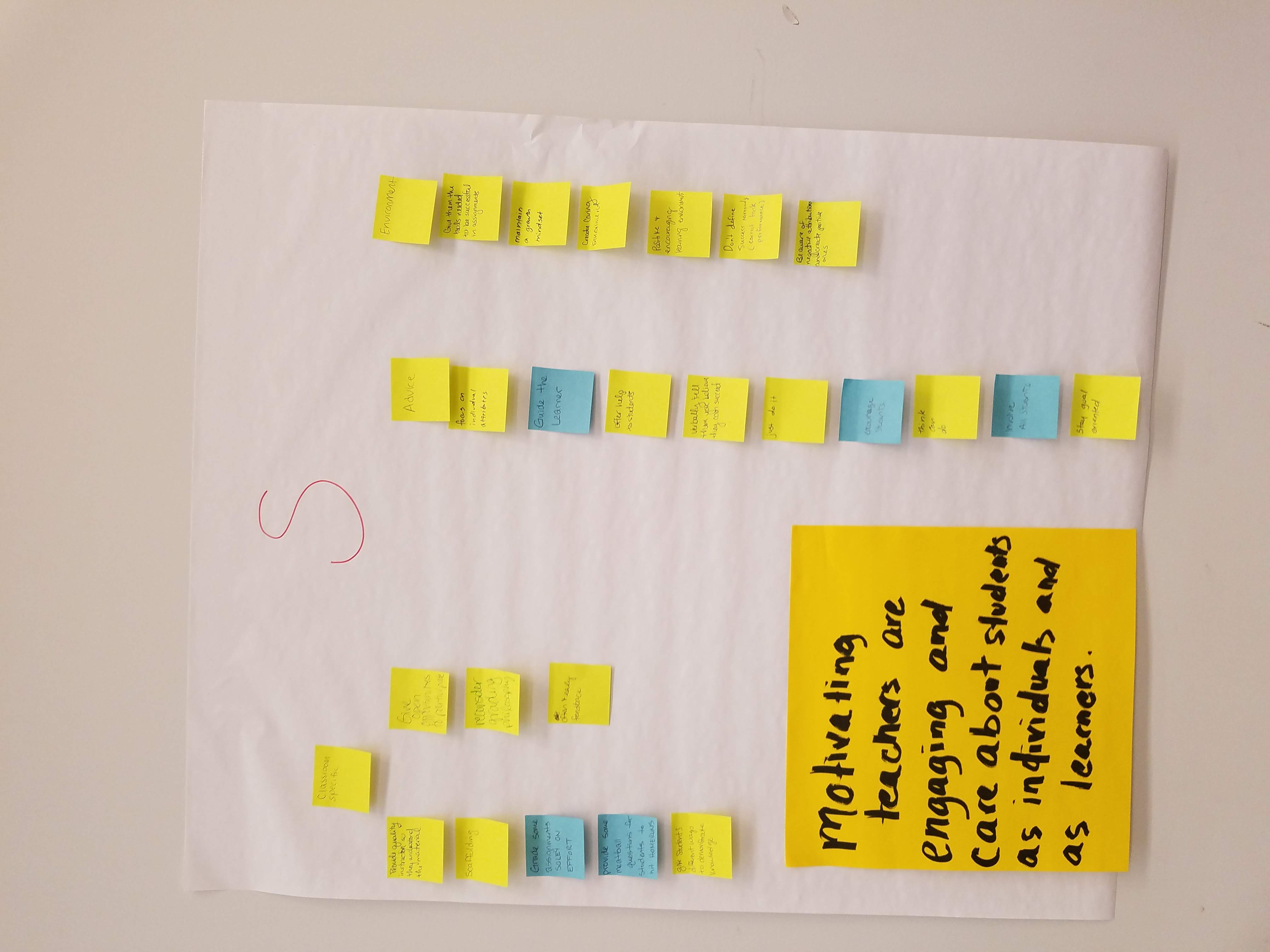

Concept or Idea Sorting

Provide students with sticky notes or cut-up pieces of cardstock/paper, about the size of small sticky notes.

Introduce a topic and ask students to write thoughts or ideas about it, based on what they know or understand. Students write one thought per sticky note. This is first done independently.

Next, ask students to share their ideas with one another in small groups, and challenge them to organize their notes in some manner that makes sense. Provide very little guidance on this - let them decide on organizational structure themselves.

Try to allow time for groups to share their structure with the class. If it is a large class, can they submit their categories or organizational description to a form that is embedded in a slide for all to view?

Use this method to lead into introducing new content. They will be interested to see whether their ideas pair up with what you share.

A twist: After they create categories (or while they are in the process), pass out on slips of paper, or share on a slide, the categories you'll be introducing for the upcoming content. Ask them to see if these categories match theirs or if they need to rearrange. Also ask if they have ideas that fit into each of your categories, or are some of yours blank?

Example (political science): What are some reasons that people might not vote? List one per sticky note.

Reflective Example (this is more for class processing): List things you did to prepare for the last exam/paper, one per sticky note.

A group's sorted sticky notes for one dimension of motivation ("S" = Success)

-

Guided Inquiry

Guided Inquiry can occur in two ways:

- Students generate their own questions prior to learning new content and use these questions to guide their learning

- The instructor creates a set of questions deliberately structured and ordered to guide students' learning from an introductory level of understanding to deeper application and transfer of that understanding.

Student-Generated Questions

Consider using the QFT Method of question generation. This helps students generate together effective questions.

Instructor-Generated Questions

Create a worksheet that builds questions, starting from easy (e.g., access prior knowledge, pull easy-to-find answers from some sample content) to more challenging (e.g., reach conclusions or implications, compare to other content, apply to a situation). This leveling-up process is known as the 5-E model of learning; click out to learn more using a framework that is helpful for guiding your question-structuring.

Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL) is a prescriptive process that has an excellent track record in the research when it comes to student learning. This method was developed in the STEM fields of higher education (though applicable to any field), and is best learned through the POGIL project's training - we strongly encourage getting it!

-

Think-Pair-Share

This method is easy to use at any time, and can be a quick one to turn to if students seem to start tuning out.

This is a 3-step process, with an optional 4th:

- Think: Ask students to take 1-2 minutes to think about an answer to a question. Encourage them to write down their thoughts; light notes is just fine for this. [This step is important; it allows slower processors time to think through the question and their responses; it also ensures everyone is considering an answer and not just riding off of what others say.]

- Pair: Students then turn to a partner and each share their responses. Encourage further discussion. This can be done in about 3-4 minutes. [Odd # of students? A group of 3 is fine if needed.] Note: Announcing to students that, when you return to the whole class, you'll assume "all hands are up" and randomly call on some people to respond can help ensure these discussions stay on topic!

- [Optional] Square: Pairs then find other pairs, to form groups of 4 (or 5). Pairs share their collective thoughts and come to some small-group conclusions.

- Share: Pairs or groups are called on to share their thoughts with the whole class. There is no need to call on every pair; randomly select some, then ask about any thoughts that are unique and weren't yet shared. Alternatively, your pairs or groups could enter final thoughts in a cloud survey, where all can view the responses; be sure to review and summarize/comment on these aloud with your whole class.

The key to making this an effective, HIP activity is in the quality of your question. Be sure you are not asking a question that is easily answered or asks for simple recall or understanding. Below are some standard, deeper types of prompts you can use:

- Compare or contrast 2 pieces of content information

- Consider how information just learned relates to other information

- Apply new information to a quick case or situation

- Present a problem similar to those solved together in class, but perhaps with a moderate variation

- Consider ways the new information can be used in a related profession

- Evaluate the new information for its usability, accuracy, bias, etc.

- Ask students to generate an image related to the content (or show a slide of an image and challenge students to consider how the content is represented by the image - works best if image is pretty random!).

The questions can also be reflective and used toward the end of class:

- Most useful information learned today

- Most challenging information learned today

- Questions you still have or that you now have, based on today's content

- One thing you plan to do to review this content later this week

-

Collaborative Testing

Assess students first individually on an exam or quiz. Then, have students work together in groups to discuss the same questions and re-answer the questions (independently or as a group). Upward differences in scores are honored with the final grade in some way (e.g., accept the new score; raise the initial score to the midpoint between initial and new score, etc.). In the unlikely event the group score is lower than someone's initial score, the highest score is maintained, making this a no-risk option.

Learn more about collaborative testing:

Whole-Class HITPs

-

Debates

Debates are a more-involved HITP and probably should be reserved for use only 1-3 times per semester. It is likely a debate will take a significant part of a class, if not the whole class time. But the learning gains and student engagement are worth it!

Debates can be arranged in a couple of ways. In either instance, announcing the debate ahead of time and encouraging or requiring some prep work (see below) is strongly advised to make the activity effective.

Select a debate topic and premise statement that allows for rich and nuanced thought. Responses should not feel easy or obvious, but should instead create tension because there is evidence from your course that might support either side of the debate.

Students' Choice

On the day of the debate, students choose which side of the premise statement (which you have provided to them) they are on: Pro, Con, or Undecided. Students sit on the side of the room designated for their choice (Undecided students sit in the middle).

Engage in a whole-class debate, asking students why they selected the side they are sitting on (or in the Undecided section). Students may get up and move positions if they change their minds; a great question in this instance is to ask what made them change their stance.

Undecided students MUST choose a side by the end of the debate!

See below for wrap-up ideas.

[A twist: Mid-debate, require students to argue the opposing side!]

Instructor's Choice

Instead of students choosing their side, randomly assign students to one stance or the other: Pro or Con. [Added twist: Could a panel of students be "judges" for this debate?]

Permit time at the start of class for each "side" to meet and organize their points. Perhaps small groups will make this more manageable in a larger class. Not only should they organize their arguments for their own side, but they should anticipate - and develop rebuttals - for arguments the other side might make.

After prep time, engage in the debate, either permitting elected spokespeople from each side (in large classes, from each smaller group?) to come up front and engage in an assertion, a reubuttal, and then a response. The flow of the debate is up to you, but going through this process several times, with several spokespeople, is likely to yield the richest thinking. You might consider pausing mid-debate for some "side" regrouping discussions. If you use a panel, they might rate the strength of the arguments, based on evidence and support (rating down for emotional or unsubstantiated claims).

Wrap up with an idea below.

Wrapping Up Debates

However you conduct a debate, it's best to leave at least 20 minutes for some final processing.

Whole-class discussion prompts might include:

- What did you notice about the ways people argued their points?

- What are some conclusions we can draw about this topic?

You can also ask for short, individual reflections - but these can also make terrific Think-Pair-Share questions or whole-class prompts (after permitting students some time to reflect and consider their individual responses). Examples:

- What did you learn about this topic that you didn't know before?

- Did you change your mind about this topic, or are you thinking differently about it? What caused this change?

- Are you able to see both sides of this debate? Does that help you feel more informed about your decision?

- What did you learn about yourself as a result of this debate? (Be prepared for responses ranging from debate behaviors to content-related insights.)

Preparing for Debates

In advance of debates, it is helpful to ask students to complete a preparatory task. The task can be done without accountability, but might be most effective if they are required to submit it ahead of the class time.

Although added effort, consider collating responses from students into a set of common points that you can hand to students on each side of the debate. [Hint: You can feed all responses from a side of the debate - yes, this is lengthy! - into a ChatGPT prompt and request that ChatGPT develop a set of themes based on those responses. This will save you a LOT of work!]

Some ideas for preparatory questions:

- Provide [3] arguments that support your [selected or assigned] stance. Please be sure to provide evidence to support each argument from our course materials or other academically responsible sources.

- What are at least 2 counter-arguments the opposing side might make? How can you rebut them, using evidence from our course or other responsible sources?

- Locate one resource about this topic that is (a) not provided in our course materials and (b) is academically responsible - a creditable organization, peer-reviewed article, etc. What new information is provided in this source that can support an argument for your [selected or assigned] stance?

-

Mock Trials

Similar to debates, mock trials require a lot of preparation and class time; this can be a good one to drop into your class around 2/3 of the way through the semester to shake things up.

What can be on trial?

It doesn't have to just be people! You can put a policy, concept, or claim on trial, or an application of material (e.g., a treatment plan, lesson plan, or other complex solution that is already "out there" to a course-related problem).

Assign sets of people to roles: Judge, prosecution, defense, various witnesses, perhaps someone representing the defendant (even if a concept!), jury. You may wish to assign multiple people to a role - such as a "prosecution team."

See preparation questions under debates for a good start. It may be advisable to allow the class prior to the trial for students grouped under each role to prepare - each role is likely to have different preparatory tasks.

This example lesson plan puts a character from a story on trial. You can use the structure for many types of trials!

Wrap-Up

See questions for whole-class processing or individual reflection under Debates, above. Many of these questions could be appropriate here: Convict or recuse? Why?

Be mindful that the activity will lose its power if you do not end with some kind of reflection and collective take-away. Save about 20 minutes of class time for this essential part of the process.

-

Fishbowls

Fishbowls can be powerful as a learning tool but also intimidating to students. Work to build a positive relationship with students before attempting this method; it is also advisable to do the fish bowl often enough that all students end up in the bowl at some point.

A fishbowl is essentially when a smaller group of students go through some sort of process, with or without instructor participation, while the rest of the class observes.

Again, remember that those in the fishbowl are in a position of vulnerability. Treat this activity and those individuals with care.

Examples:

- Role play a particular type of interaction or applying a skill set

- Work with a team to solve a problem or address a case study together

- Share a group project draft with the instructor and receive feedback

- Participate in a peer feedback session with one another

- Discussion of an open-ended and debatable question

The fishbowl can be inherently interesting for the rest of the class to observe, but the impact of this activity is when ALL members of the class have a role or function.

Thus, for those NOT inside the fishbowl, assign different "observer" roles. You can assign the same role to several students. Here are some examples:

- For a role play or case study fishbowl, the roles of other people who might be impacted by the outcome. For example, if the fish bowl group is developing a lesson plan for a group of English Language Learners, some observers might be the "students in the ELL class" - would the lesson be engaging? Paternalizing? Helpful?

- Process observer: How did each person in the bowl interact? Did they follow their role well? Did they respond to feedback appropriately? What were the group dynamics? (Some of these could be broken up for Process Observer 1 and Process Observer 2)

- Content observer: What content was used? Was anything left out? Does the solution/content used seem effective?

- Implications finder: Based on what is happening in the fishbowl, what can be concluded... about how groups of people work together? About the content? About what might be left to learn?

If space permits, encourage your observers to walk around and jot down notes as they observe (be sure they have clear instructions about their role and what they are watching for). Movement can be helpful for observation. They should not speak or interfere with the process inside the fishbowl.

Post-Fishbowl Reflection

As with most activities, the learning effects can fall flat if a wrap-up discussion is not included. Once everyone is settled back in their seats, ask each observer group what they observed (as a pre-step to this, you might have these groups, and the fishbowl group, meet to share notes about what they observed or experienced in the process).

Getting the observers' varied perspectives on what happened is powerful in learning from this activity.

Follow up with a short individual reflection you request from each student, as an "exit ticket" (e.g., short paragraph they hand you on the way out the door) or as a short reflective paragraph they turn in digitally within the next few days. Reflection questions might include:

- What did you learn from this fishbowl that you hadn't thought of before?

- Now that you have done this fishbowl, how might you use this information differently, or what might you watch out for?

- What feedback did those in the fishbowl receive that you can learn from? (For fishbowl recipients: What feedback was most meaningful or useful to you)?

- What did you learn about the value of feedback? What did you learn about the best ways to deliver or receive feedback?

Variations

Fishbowls can vary in lots of ways. Explore a few other websites that describe the technique below:

- Learning for Justice website

- K. Patricia Cross Academy video

- Western Sydney website - includes ways to do this online

-

Jigsaw

With the Jigsaw technique, unit or class-day material students are learning is divided into roughly 5-6 topics or chunks.

Students are first assigned to Expert groups, and each Expert group is assigned a different topic. In their Expert groups, they either review together the main points of their topic (if pre-assigned before class) or learn about and pull the main points during their time together. Comprehensive understanding or their topic is essential. [Twist: Ask Expert groups to develop quiz or exam-type questions about their topic.]

Next, Expert groups are splintered and Learning groups are formed, with at least one representative from each Expert group in the Learning groups. (Now you see why it's called Jigsaw!). Each Expert member teaches their Learning group the topic about which they have developed expertise. [Could they share or test their group using the quiz questions their Expert group developed?]

The goal is for every Learning group to now know all of the material well. An optional and optimal next step, although time-consuming, is for Expert groups to reform and share their learning about all of the other topics. This helps fill in gaps from any potential "poor teachers" they might have had in their Learning groups.

Expert and Learning groups could be assigned and used throughout the semester for more than one Jigsaw event (the "expert" topics can change or be added as you advance through the material.) You and your class will find that the first Jigsaw is messier, but the process becomes smoother once the class has done it one time.

One possible - non-graded - light competition for the class could be to see which Learning group gets the highest average quiz/exam score. It's important in this instance to not post individual scores; this option is not advisable if the process somehow exposes a student's outlier performance.

We will continue to add to and edit this page, so be sure to check back periodically for updates!

Stout Drive Road Closure

Stout Drive Road Closure